THE ABIDING INTEREST, DOUG ARGUE’S FISH PAINTINGS

BY J.C. HALLMAN. August 12, 2022

First off, stop saying tropical fish. Instead, say ornamental fish. And before you get your nose in the air about it, please note that in 2021 the ornamental fish market in the United States was valued at $5.4 billion, and is expected to increase at an annual rate of 8.5% until 2030.

Duly chastised, let us now turn to Doug Argue’s vast canvases stuffed with shimmering, bullet-shaped forms—to guess a species is to miss the point, though the dense cramming-in of shapes suggests sardines—which regardless of the title of a show or any particular work will come to be known as the artist’s “fish paintings.” To be sure, these paintings will be sold, as though hooked and dragged from the artist’s inner ocean, to be distributed to markets across the world. Nevertheless, I will assess the works as a whole—as a school.

Aquarium Visit: Girl and the Grouper :: Oil/Canvas :: 60 x 84 in. :: 2021-2022

One painting stands out, starkly, from the rest. A maximalist splash of color immediately draws attention to this work, and variety of hue is matched by a variety of aquatic species, a grouper-like beast dominating in the center, flanked by gars, a heavenly host of angelfish, a few scissor-tailed minnows—the kind of fish one is more accustomed to seeing behind glass, in aquariums. Indeed, the fishes’ environment—and, apart from this image, Argue’s fish paintings will offer precious little by way of environment—is as evocative of a coral reef as the diverse plants and stones used to decorate fish cages: ornaments for the ornamental fish, as it were.

And then, as though to confirm a suspicion just taking the form of words, the negative space at the right side of this key canvas—a blackness like the black that blue water becomes as it descends into bottomless ocean trenches—takes shape: a young girl, striped shirt and skirt, eye to eye with the grouper beast, her hands pressed against the glass that separates them.

The question of the fish paintings becomes this: Are we looking at nature, or is nature looking back at us?

Untitled :: Oil/Canvas :: 36 x 50 in. :: 2021

Henry James, in a letter to his philosopher brother, once wrote of Tintoretto: “I’d give a great deal to be able to fling down a dozen of his pictures into prose of corresponding force & color.”

Most of Argue’s fish paintings exhibit force and color, most depict crowds like Tintoretto’s vast (and I assume allegorical) assemblages of humanity, and several approach a Tintoretto-like scale, one the size of a garage door, and another also the size of a garage door—but a garage for two cars.

Fish School 2 :: Scale :: Oil/Canvas :: 8 x 10 ft. :: 2021

I tried counting the fish in one painting, got to a thousand, and decided that was enough.

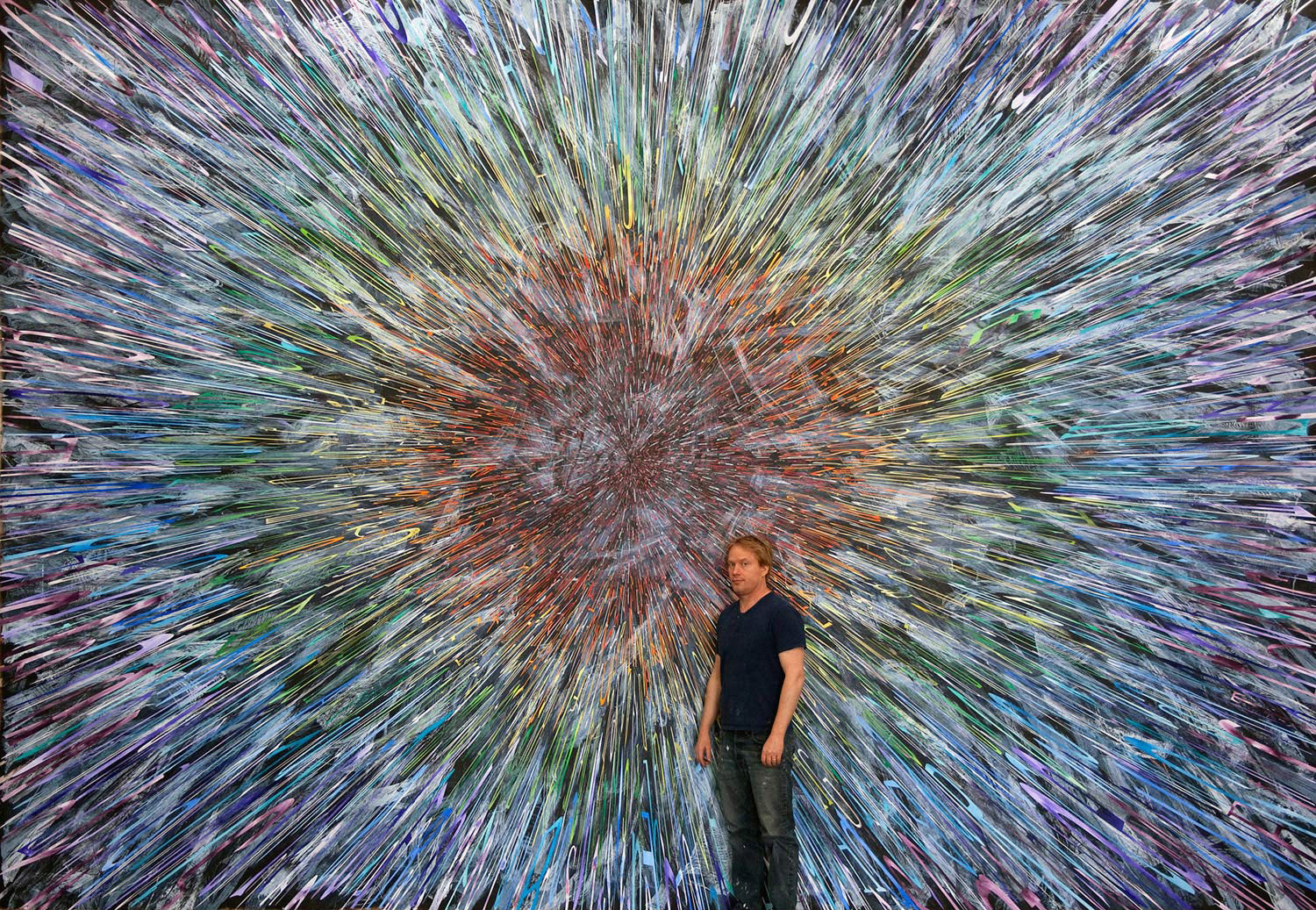

Untitled :: Scale :: Oil/Canvas :: 144 x 216 in. :: 1994

Genesis :: Scale :: Oil/Linen :: 160 x 230 in. :: 2009

The rendered world is both tamed and wild, familiar and entirely alien.

Fish school 3 :: Scale :: Oil/Canvas :: 100 x 120 in. :: 2021

Color is irrelevant, or beside the point. Fish tend to be gray, but Argue’s fish feature streaks of blue and red, or yellow tails. His water may be anything from white to black, mostly pale blues and greens because water absorbs the red part of the spectrum. The paintings collectively suggest a prismatic effect in lieu of a clearly defined source of light.

Close inspection suggests some idea of subversion informed the act of painting itself: it’s not always clear that the artist first decided on a background, and then installed his schools on top of it. The fish came first, and their element appears to have been meticulously poured in, after the fact.

There is a photograph of the artist taken after the fish paintings were hung for a show in New York City: he stands to one side of a large canvas, facing away, captured in a moment of final touch-up on the flank of a fish—one of a school of fish that dwarfs him. Moments of last-minute adjustment are, I suspect, common in the world of exhibitions, but there was something about this image, the artist in his uncertainty, that I found touching. It is unclear why this particular fish would have stood out to Argue as needing additional detail at the last minute, as appearing unfinished.

If this one fish wasn’t done, how could any of them have been done?

J. C. HALLMAN

J.E. Hallman is an American author, essayist, and researcher. His work has been widely published in Harper’s, GQ, The Baffler, Tin House Magazine, The New Republic, and elsewhere. He is the author of six books, and his nonfiction combines memoir, history, journalism, and travelogue, including the highly acclaimed B & Me: A True Story of Literary Arousal, a book about love, literature, and modern life. jchallman.com