FROM IMMIGRANT STORIES TO ENVIRONMENT DREAD, EXPO CHICAGO GETS DARK

The Midwest’s mega-fair seems less concerned with the bottom line, making space for politics.

BY CLAIRE VOON. September 15, 2017

BY CLAIRE VOON. September 15, 2017

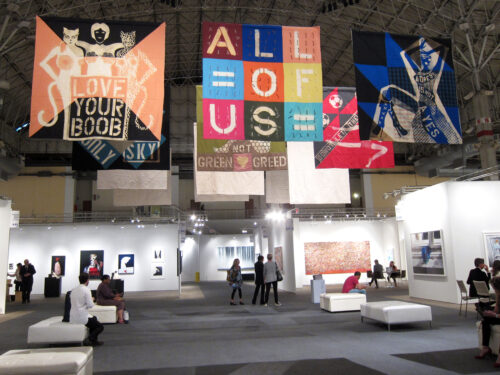

EXPO Chicago, with hanging installation by Wang Du (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

CHICAGO — One of the most startling works at this year’s EXPO Chicago is a lifesize guillotine by Piero Golia, at the top of which is lodged a steely-looking blade, ready to drop. “Untitled (Evil exists where good men do nothing)” fit its surroundings well when installed in an old courtyard two years ago during Basel, but currently confined within Gagosian’s booth at a convention center, it makes for an anachronistic curiosity amid other contemporary works at this major Midwestern showcase.

It is but one of the many pieces at the Navy Pier’s Festival Hall — the fair’s nucleus — that stands out for being exactly what you wouldn’t expect at a market-driven art show. Unlike your typical New York or Miami Beach fairs, EXPO Chicago seems more inviting for exhibitors to focus less on the “commercial” part of having “commercial spaces” and instead show work that’s unusual and, at times, plain weird. There is, notably, an almost complete lack of selfie-inviting mirrored pieces, yawn-provoking minimal sculptures, and flashy neon art. The 135 participating galleries — 19 of which are local — largely give us works that are fresher and spunkier. Among booths not to be missed are those of Chicago mainstays Rhona Hoffman and Kavi Gupta as well as the German dealer René Schmitt, who is showing works by Lorraine O’Grady and A.R. Penck.

The most thoughtful display, though (and perhaps even the best booth) is that of the Chicago Artists Coalition. The very pink installation by Mexican-American artist Yvette Mayorga is a saccharine but bitter vision of the American dream, featuring Rococo-inspired paintings and sculptures that speak to the traumatic experiences of Mexican immigrants. An ornate, innocent-looking wallpaper reveals repeating figures of ICE agents; a recurring image of a car with a body in its trunk is an unflinching portrayal of how people need to put themselves in danger as they seek better futures. You don’t typically see political work this personal and raw at art fairs, much less by young artists of color. Can we get more of this, please?

A number of standout booths are similarly transportive in how they determinedly shed their white walls for zanier alternatives. Taking the cake for the strangest is R & Company, who presents a delightful show of Italian Radical Design from the 1960s and ’70s. The eye-catching, grid-patterned stage feels like a three-dimensional, blown up Surrealist painting (or an emoji wonderland), where coatracks resembling cacti and the famous, lippy “Marilyn Bocca Sofa” are accompanied by giant blocks of cheese (Swiss). Galerie Gmurzynska, too, seems bent on eschewing the typical fair experience despite its show of more predictable works by artists including Yves Klein, Laszlo Maholy-Nagy, and Fernand Léger. At its center are four decadent, cabana-like enclosures sewn from an array of ornate fabrics that each shelters an artwork, like an illicit secret. Designed by Antonio Monfreda, the luxurious tents are meant to offer viewers a private, quiet moment with the works — and as a nice, added touch, scent sacks are sewn into the soft walls to emit soothing fragrances. It’s a mode of encounter that’s memorable for its mystery and pace.

What contributes significantly to EXPO Chicago’s overall sense of thoughtful curation are the Special Exhibitions booths scattered throughout the fair, presented by non-profits, museums, and art organizations. The Chicago Artists Coalition’s show is one of these memorable displays that introduce timely social issues to this premier event, along with Itamar Gilboa’s “Food Chain Project,” a portion of which is presented by Tamar Dresdner Art Projects. The sculptural spread of foodstuffs is overwhelming, and intends to raise awareness of global issues such as hunger and obesity, with proceeds from any sales going toward Food Tank. A number of works also grapple with environmental concerns, from “A Library of Tears” — a grim yet graceful display of manmade pollution by Artadia awardee Claire Pentecost — to “White Wanderer” — a meditation on glacial collapse by local duo Luftwerk, who recently unveiled a companion soundscape by the Chicago River.

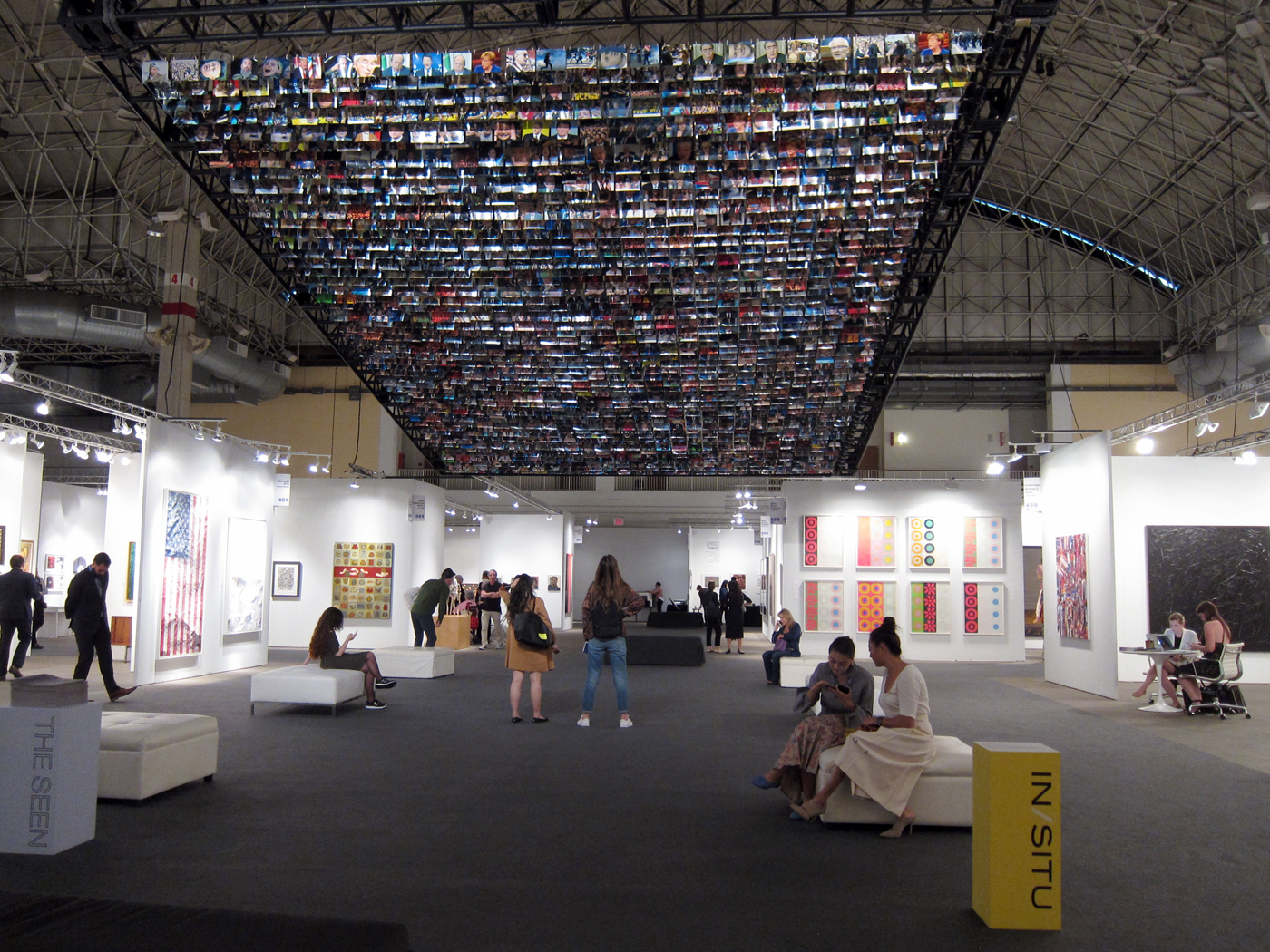

Then there are a handful of works that respond more specifically to the dark, disturbing days of our time. I spotted just one Donald Trump-inspired piece, a painting by Doug Argue at Marc Straus, which depicts the President frozen in a literal tweetstorm: Trump, shown in the infamous pose he made to mock a disabled reporter, is surrounded by fragments of his online rants, which swirl to form a nauseating vortex. More conspicuous was Anton Kern’s installation of large, square banners by Lara Schnitger, which hangs over an expansive seating area as part of the IN/SITU program. Schnitger’s “Suffragette City,” originally made for a 2015 performance, presents physical signs of the time, with each graphic banner incorporating feminist phrases like, “A Dress is Not a Yes.” The rallying cries are especially striking in this sterile setting, loud and defiant in both tone and design.

Works by Doug Argue at Marc Straus

A statement you can’t miss is “Laocöon” by Sanford Biggers, courtesy of Monique Meloche. The 30-foot-long, inflated sculpture depicts a black man lying on his front, appearing to breathe as an air pump continuously fills and deflates the figure slightly. Wall text lets you know that this refers to Bill Cosby’s Fat Albert character — and thus addresses the rise and fall of his career — but also acknowledges that the piece stands as an uncomfortable reminder of how we are “confronted almost daily” with news of African Americans being killed by white police officers who typically go unpunished. Last year, writing for ARTNEWS, Taylor Renee Aldridge called out the problematic placement of this piece when on view at David Castillo Gallery during Art Basel Miami Beach. In that commercial, white-walled context, she wrote, the sculpture was just one of many examples of artworks about black bodies that risk becoming “a provocation marketed for consumption, rather than a catalyst for social change.”

At EXPO, “Laocoön” is still being shown in a commercial space, but rather than placed within a booth, it is part of the IN/SITU program, an exhibition curated by Florence Derieux that features site-specific works installed around the Navy Pier. Biggers’s sculpture is the sole occupant a room to the side of but open to the main arena, a carpeted hallway surrounded by windows that features some stairways. Unlike in Miami Beach, the figure looks toward the main thoroughfare, instead of a wall. Here, he personifies a man who has just collapsed in a lobby from some unseen blow, and left alone. The piece is disturbing — some may say triggering — for the violence it immediately evokes. For as cartoonish as the man’s expression is, it is a face that confronts passersby, and one that’s part of a slowly heaving human body. “Laocoön” is impossible to avoid, as it lies near a busy intersection in the fair’s layout. But rather than just spectacle, or backdrop to a marketplace, the sculpture implores engagement beyond just looking. The piece questions whether people will stop when confronted with a black body slumped on the ground — and will they then acknowledge the brutalities inflicted on these bodies daily? Maybe it’s a naive attempt to engage fairgoers as they run around, perhaps with champagne in hand. But at an art fair, where you don’t expect to find politicized spaces, much less ones this conspicuous, that chance for reflection is something.